The role of women in Ireland, 1870-1914. Perspective: Economy and Society

You may also like:

The Status of Women

Until the 1860s, women had to give up their property, including wages and children, to their husband when they got married and it was much more difficult for a woman to get a divorce than for a man.

Women did not have the right to vote, hold public office or attend university and girls’ secondary schools were few in number.

A lot of poorer women worked before they got married as domestic servants, on farms or in factories.

Middle-class women didn’t work before marriage but were often forced to find work as a dressmaker or governess if they became widowed or never married and married women often worked in their husband’s shops, businesses and farms.

Women who stayed at home to raise children were not considered to be workers as they were not paid to care for their family.

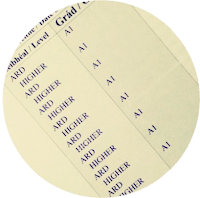

1871: Census Commissioners ordered that women working on their family farm or business were to no longer be considered as workers and be referred to instead as “domestic workers”.

1881: Women who worked in the home were further re-classified as “indefinite and non-productive”. Many English-speaking Irish women fled to America, Britain and Australia where they had better job prospects than in Ireland, and others got involved in charity work in orphanages, prisons, homes for prostitutes and the inner-city slums.

Catholic nuns also ran schools, orphanages and hospitals and many women likely joined convents because nuns had much more influence and independence in society than other women.

|

| Andrew Wyeth. Image credit: The New York Times. |

Isabella Tod

In 1864, Belfast woman Isabella Tod and other middle-class Protestant women began to protest against gender-based discrimination as a result of the Contagious Diseases Act which ordered the imprisonment of prostitutes with sexually transmitted diseases while their male customers were allowed to walk free.

In reaction to the unfair double-standard of the Act, Tod led women’s rights activists in a campaign that succeeded in getting the Act overturned.

Tod in Belfast and Anna Haslam in Dublin then started to campaign for married women’s right to property with Tod speaking of the frustration of women who had to hand their wages over to their husbands to buy alcohol and the campaign successfully led to the introduction of 3 acts to give women the right to property.

Suffragists

1871: Isabella Tod founded the Northern Ireland Society for Women’s Suffrage to campaign for women’s right to vote and Anna Haslam and her husband set up a similar organisation in Dublin.

Until her death in 1896, Tod travelled around Ireland giving speeches and handing out leaflets to rally support, gaining a following of middle-class protestant women who organised meetings and petitions.

1900: more women gained access to higher education and the well-paid jobs and money that came as a result of this gave many women the confidence to stand up against the government and demand equality.

Both Catholic and Protestant women of all social classes began working together to demand gender equality.

1898: the Local Government Act gave Irish women the right to vote in local council elections and hold positions on councils and Haslam’s Irish Women’s Suffrage and Local Government Association (IWSLGA) began to encourage women to use these new rights.

1899: 35 women stood for and won seats in local council elections and women across Ireland began to take a keen interest in politics.

|

| Andrew Wyeth. Image credit: The New York Times. |

Inghinidhe na hÉireann

1900: Queen Victoria visited Ireland for the last time and nationalists Maud Gonne and Jenni Wyse Power organised a demonstration against British rule in Ireland.

Gonne and Wyse Power then set up a nationalist women’s organisation called Inghinidhe na hÉireann to encourage people to buy Irish produce and organise free Irish, history and music classes, céilídhe and plays where many of the Abbey Theatre’s actresses first took to the stage.

The Inghinidhe also travelled to poor schools in Dublin city and provided the children with free meals.

The organisation was strictly republican and was involved in the foundation of Sinn Féin, with Wyse Power was on the Executive of the party.

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington

By the 1900s, women had all the rights that they had campaigned for except the right to vote in parliamentary elections.

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, wife of feminist campaigner Francis Sheehy Skeffington, joined the IWSLGA but was not impressed with their patience and gentle policies.

In Britain, militant feminists like Emmeline Pankhurst and the suffragettes started to hold disruptive demonstrations that would interrupt political events and forced politicians to listen to their demands.

The Labour Party were united in their support of women’s rights but Liberals, Conservatives and the Home Rule Party were split between those who supported the campaign and those who feared the consequences of female MPs.

1910 – 12: Women in Britain won the right to vote through a number of acts.

1908: Sheehy Skeffington was inspired by the success of the British feminists and set up the Irish Women’s Franchise League (IWFL) as a much more militant organisation that organised marches and speeches in support of female suffrage.

Women and the Home Rule Bill

1910 – 12: Home Rule seemed inevitable as the British Liberals became dependent on the Home Rule Party and the IFWL began to organise protests to demand that women have the right to vote in parliamentary elections under the Home Rule government.

British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith and Home Rule leaders John Dillon and John Redmond were all opposed to women’s franchise and claimed that its introduction would “destroy the home, challenging the headship of man”.

June 1912: a huge meeting was held by women’s rights organisations in Dublin and demanded that the Home Rule Bill be altered to include women’s rights.

Militancy

At the June meeting, the IFWL decided to take militant action against the government and the next day, Hanna Sheehy Skeffington and a small group of women smashed the windows of government buildings before being arrested and sent to prison.

Anna Haslam led Irish feminists in protest against the arrests and Jennie Wyse Power sent the prisoners meals but the majority of people condemned the violence.

July 1912: three English militant feminists attacked Asquith while he was in Dublin, accidentally hitting Redmond with an axe and attempting to burn down the building where he was going to speak

Asquith’s attackers were arrested and went on hunger strike in prison, joined by Sheehy Skeffington in an act of solidarity.

The IFWL continued its militant campaign while moderate feminist groups denounced their actions and other nationalist groups took to attacking women’s rights meetings.

1912 – 14: 35 Irish women were sent to prison and twelve of them went on hunger stroke, causing uproar when the government started to force feed them and the Cat and Mouse Act was passed which allowed women to be released from prison when they became ill from hunger striking, only to be arrested again once they had recovered.

Nationalist vs Unionist Women

The Home Rule Bill divided the once united women’s rights movement between nationalists and unionists.

Jennie Wyse Power and the nationalists were focused on winning Home Rule and set up Cumann na mBan to support the Irish Volunteers.

Unionist women wanted to maintain the union with Britain and 45,000 joined the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council.

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington and Anna Haslam initially remained focused on winning women’s suffrage but during WW1, Sheehy Skeffington campaigned against Irish recruitment to the British Army and became a militant republican when her husband was murdered by a British soldier during the 1916 Rising.

|

|

Leaving Cert Sample Answers and Notes

|